Topic of the month: Russia’s HIV and Drug Policies: Misguided and Ignorant

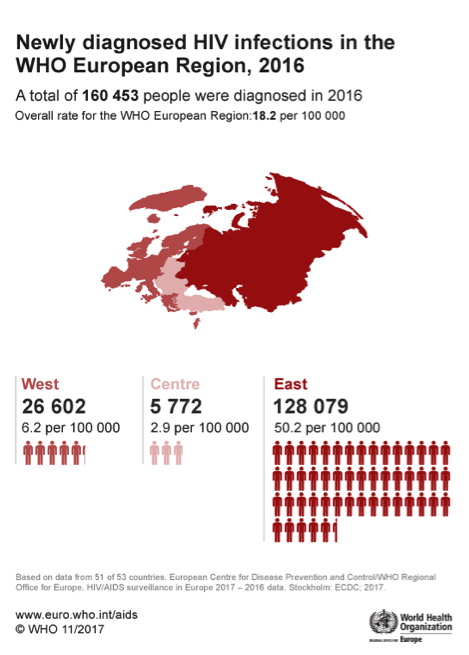

In 2016, new diagnoses of HIV in Europe reached a new high. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organisation (WHO) speaks of alarming numbers and a growing epidemic. Eighty percent of new infections occurred in Eastern European countries. This is the highest annual number that has ever been diagnosed in Europe.

Russia. (Photo: Mariano Mantel/flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

This trend must be stopped or the end of AIDS by 2030 is not achievable, according to Zsuzsanna Jakob, WHO Regional Director for Europe, commenting on the report. (Europe's HIV problem is growing at an alarming pace. World Economic Forum 2017)

Many experts have been warning for years about the effects of the drastic rise in new HIV infections in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The increases in these regions bucks the worldwide trend which records a decrease in new infections of around one third. According to the UNAIDS report of 2015, only 67% of all those living with HIV in these regions know of their status; 21% are being treated; and 19% are below the detection level of the viral load – this is far below the 90-90-90 global targets by 2020. (AIDS in Eastern Europe and central Asia: time to face the facts. Lancet 2016)

Above all, Russia is seeing the most rapid spread of the epidemic. The country has the highest HIV-infection rate in Europe. The disease is now running unchecked. In 2016 it is estimated that 275 new cases were diagnosed every day – a total of 103,000 new infections. And experts estimate that the number of undiagnosed infections is significantly higher.

And yet HIV is a taboo issue in Russia. Although the epidemic has now reached the middle classes, the government is only reacting in a half-hearted way and almost nothing is being done to educate the Russian population about the dangers of HIV. Conservative politicians declare AIDS to be an invention of the West and a part of the “information war” that “the West” is waging against Russia. (German AIDS Service Organization: Russian HIV Policies: Immune against Common Sense?)

Marginalised Sections of the Population

For the ‘key groups’ in which the epidemic is chiefly concentrated, this attitude is proving fatal. Homosexuals (men who have sex with men – MSM), sex workers and drug users belong to the most ostracised and persecuted groups of people in Russian society and have insufficient or no access to adequate HIV prevention and treatment.

Homosexuals: violence and human rights violations against homosexuals are omnipresent. The police usually do nothing to protect these people – there are no criminal prosecutions. Although 1993 saw the repeal of a law dating from the Stalin era which sentenced homosexuals to five years in jail, in 2013 the Russian government decreed an act which renewed discrimination against homosexuals: since then, it has been against the law to talk about homosexuality in a positive way in the presence of minors. In 2017 the European Court of Human Rights condemned Russia for its anti-gay laws. According to the judges in Strasbourg, the ban on “Propaganda for Homosexuality” contravenes the laws on freedom of expression and prohibition of discrimination. (NZZ: Strasbourg Condemns Moscow’s Homophobia 2017)

Sex workers: in today’s Russia, sex workers also belong to an ostracised group. One of the most effective methods of HIV prevention is to recommend that sex workers use condoms. But not in Russia: condoms are not only confiscated; people who carry them are automatically branded prostitutes and run the risk of being imprisoned. It is downright cynical politics: the police are promoting unprotected sex and hence the spread of HIV.

Drug users: in spite of the persecution of homosexuals and sex workers, there is no doubt which group in Russia is experiencing the worst repression – it is the drug users. According to estimates, of the HIV-positive people in Russia, 60% are addicted to drugs. However, many do not know their status because fear of reprisals and being put on a drug register mean addicts do not get themselves tested. (PLOS Medicine: The expanding epidemic of HIV-1 in the Russian Federation, 2017)

"Enough is enough – Open your mouth!", Demonstration against homophobia in Russia (Photo: Marco Fieber/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Russia’s Policy: “zero tolerance of drug users” instead of “zero tolerance of drugs”

With over 5,000 deaths per month, Russia’s drug problem could be stopped with measures successfully undertaken in many other countries such as the provision of clean needles and syringes and replacement therapy with methadone. Russian policies alone deny any such substitution therapies on threat of punishment and offer almost no other damage limitation methods. In Russia, drug addiction is seen as a mental weakness and personal failing that is best treated with withdrawal and work camps. In the best case scenario, drug addicts undergo a three to twelve-day withdrawal in one of the many state-run withdrawal centres and are then treated for several months in a walk-in rehabilitation centre. This approach is broadly unsuccessful: 90% of those undergoing such treatment resume taking illegal drugs within a year.

The chief problem of Russian drug policies is their focus on withdrawal and the denial of an adequate rehabilitation or reintegration programme. This leads to drug addicts willingly or unwillingly turning to obscure methods such as seeking out traditional healers or referral to clinics which are infamous for particularly inhumane and brutal practices: in some institutions, people have until recently been tied to their beds, whipped or treated with electric shocks. The shock they suffered was supposed to result in patients spending the rest of their lives “clean”. (New York Times: In Russia, Harsh Remedy for Addiction Gains Favor, 2011)

Internationally expressed criticism of such restrictive drug policies gains no traction in Russia: the Ministry of Health has speciously announced that they are concerned for the health of those affected and therefore are eschewing the treatment of one drug with another: a method whose success, incidentally, has not been scientifically proven.

Such arguments are contradicted by every medical institution including the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNAIDs because a daily dose of a methadone pill puts patients in the position to return to their jobs and lead a largely normal life. They and their families also profit from the substitution in other ways: the single fact that they are no longer injecting drugs and thus avoid being infected by HIV is already a bonus. Obviously methadone is also a drug, but one with a profoundly different effect to something like heroin. It is metabolised more slowly and thus prevents the craving for heroin. It breaks the vicious circle of the illegality and the precarious financial situation that the constant search for heroin involves.

"Enough is enough – Open your mouth!", Demonstration against homophobia in Russia (Photo: Marco Fieber/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

An Unbearable Situation also in the Prisons

It is not just the refusal of treatment that is causing concern but also the entirety of repressive state measures against drug users. The possession of a small amount of drugs is already enough to be arrested by the police. The prisons are now overflowing with prisoners who are not only suffering from addiction but also from wide-ranging health problems: HIV, hepatitis C and tuberculosis are serious diseases from which many prisoners suffer at the same time without receiving adequate treatment – and many pay with their lives.

Michel Kazatchkine, former Global Fund Director and now Special Adviser to UNAIDS, also criticises Russian drug policies for taking the wrong path. It is obvious, they have failed. However, the Russian politicians are vehemently sticking to them.

A Crippled Civil Society

Activists and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) like the Andrey Rylkov Foundation who are fighting against the spread of HIV and for a more humane drug policy in Russia are increasingly experiencing harassment which prevents them from undertaking work such as, for example, distributing condoms or clean syringes. Censure by the Russian state has led NGOs receiving money from abroad to being summarily declared “foreign agents”, as the Russian journalist, activist and former employee of the Andrey Rylkov Foundation, Alexander Delfinov, reported in an interview with Action against AIDS Germany. To him, it is clear that groups on the margins of society, such as drug users, are not wanted by the Russian system and that “people are essentially glad when those people die out”. (Action against AIDS Germany: Dangerous and Inhumane – Russia’s Repressive Drug Policies)

Despite all the Warnings, Heading for Disaster with their Eyes Open?

In 2016 the Russian health system adopted a new strategy paper in the fight against HIV; and Russia’s participation in the UN High Level Meeting in New York on ending AIDS in June 2016 also allowed hope that these were more than mere gestures of goodwill. But director of the Russian AIDS centre, Vadim Pokrovsky, remains sceptical and sees continuing political apathy about particularly at-risk groups. He also laments inadequate financial efforts in the fight against HIV/AIDS. The budget is not enough to finance the ART treatments, which in Russia are still very expensive, for all patients. And there are also the cuts made by international funders like the Global Fund. Potentially three out of four patients receive no or inadequate treatment. This means only 25% of infected people in Russia are receiving treatment; by 2020 it is supposed to be 60%. The UNAIDS goal, however, is that 90% of infected people should be receiving treatment by 2020.

The HIV and drug problem in Russia is complex and difficult to analyse. An inhumane policy, an opaque and non-transparent data situation and a geographic proximity with weak border controls to one of the largest heroin and drug-trafficking routes in the world are all exacerbating the alarming situation. There are sufficient indications to show that the Russian HIV and drug epidemics are running unchecked and are growing worse. A middle-income country like Russia should and must undertake vastly improved efforts to prevent this and to protect its citizens.

Martina Staenke

Communication Manager, Medicus Mundi Switzerland

mstaenke@medicusmundi.ch