March 2018 - Topic of the month: Gender-Based Violence and HIV/AIDS in South Africa

Violence against women and girls is a structural problem in South Africa. It is a central cause of the high rates of HIV infection. Medical and psychological treatments pose great challenges to health workers because physical injuries and traumatisation exacerbate existing illnesses that are particularly caused by poverty and infrastructure deficiencies. All these are consequences of the racist apartheid system and the slow-moving process of change since the introduction of democracy in 1994. A number of state agencies and, above all, innovative women’s and health organisations are working hard to overcome these complex problems. (By Rita Schäfer) Photo: A demonstration of female AIDS activists © Rita Schäfer.

July 2018 will see the celebration of Nelson Mandela’s 100th birthday. He is regarded as a symbolic figure of the new South Africa – the reconciler who sought to implement human rights and human dignity. During his 1994-1999 presidency, the new constitution was drawn up and adopted. Coming into force at the beginning of 1997, it encompasses the right to health, protection from violence, and gender equality. Traditional and religious discrimination against women officially came to an end; thus, in the new South Africa, wives married according to traditional law are now recognised as full legal persons in their own right and are no longer subjugated to their husband as the head of the family – a subordinate status which, incidentally, was shared by white women until 1984. The militarised apartheid society established martial constructs of masculinity and legitimised violence as an instrument and expression of male power. In this way, power structures and gender hierarchies were manifested in the public and private spheres.

The introduction of democracy in 1994 and the new constitution intended to overcome such discrimination for all women, independent of their skin colour or background, since proprietary sexual behaviour, inequalities of power and dependencies are recognised as reasons for sexualised and gender-based violence.

The South African constitution intends to curb all this and to improve the legal position of previously marginalised groups. It laid the foundations for the equal treatment of homosexual people before the law in order to overcome homophobia and improve such people’s access to the health sector. With this, the course was set for protection against HIV infections and for the treatment of HIV-positive and AIDS patients. However, the implementation of these constitutional principles is proving to be challenging and filled with conflict.

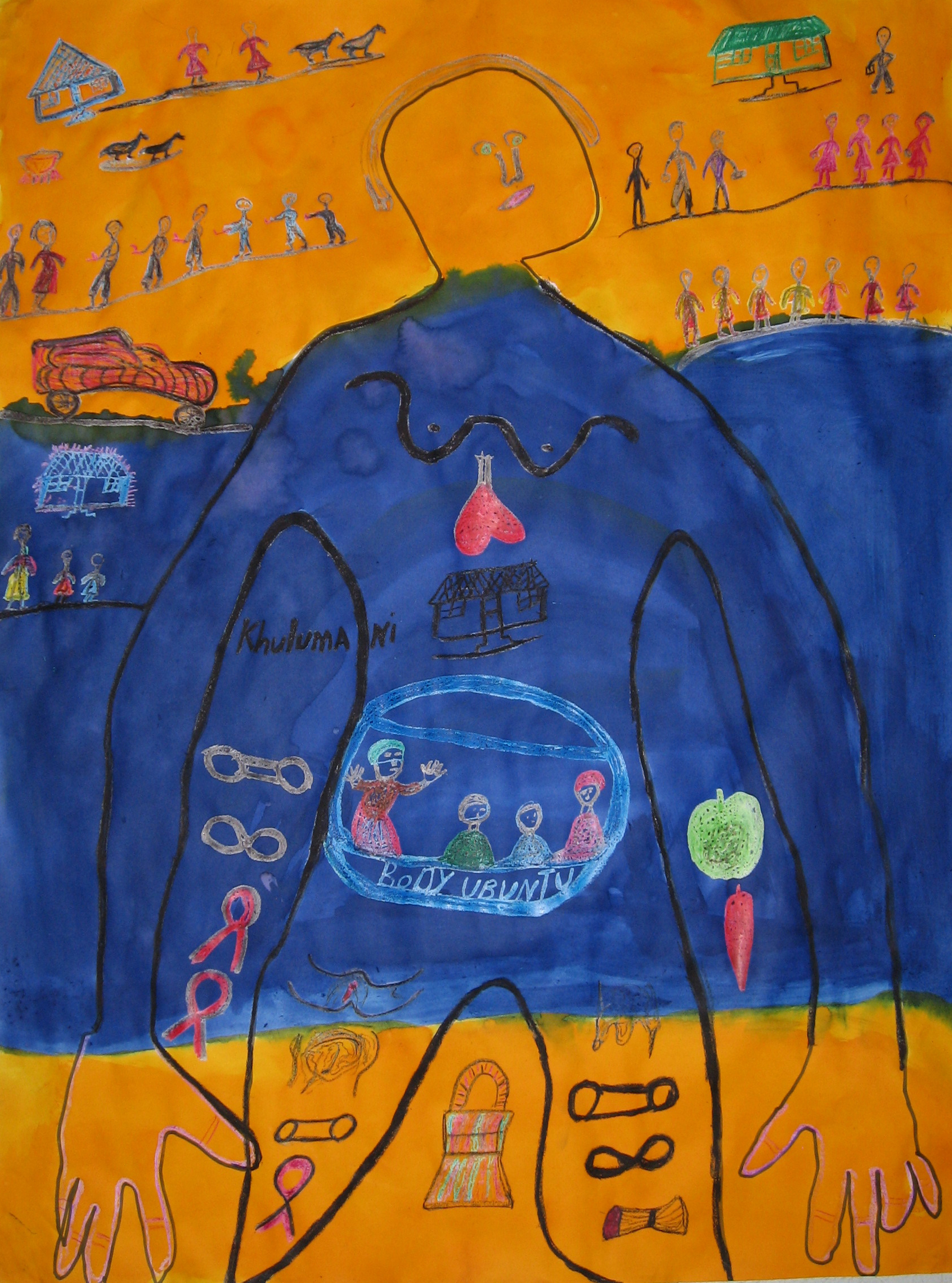

Body maps: Khulumani support group. Photo: Rita Schäfer

Fatal HIV/AIDS Policies

HIV/AIDS became a political issue under Nelson Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki. As president of South Africa from 1999 to 2008 he sought advice from so-called ‘AIDS dissenter’ from the USA who denied the connection between HIV and AIDS. For Mbeki, AIDS was a disease of poverty. Rather than anti-retroviral medication, his health minister Dr Manto Tshabalala-Msimang recommended garlic, beetroot and olive oil as cures – all non-South African products which, as expensive imports, were unaffordable to the poverty-stricken majority of the population and were of no help whatsoever to HIV-positive people. The latter only gained access to anti-retroviral medication when the non-governmental organisation Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) went to the Constitutional Court. TAC and the ruling judges contributed decisively to the implementation of the right to health in 2001/02: following the court case, state health institutions were obliged to treat HIV-positive people with anti-retroviral medication. However, in practice this remained difficult in many places.

At the same time, under President Mbeki the newly established governmental gender committees, intended to pave the way for greater gender equality and thus have a preventative effect against violence, were poorly equipped. In addition, they ignored men as a target group with the result that, for years, no programmes existed to integrate men into the fight against gender-based violence. Under pressure from the United Nations’ Commission on the Status of Women, a meeting was finally set up in 2004 to discuss the inclusion of men in the state-run gender programmes. However, at subsequent conferences representatives of a conservative Christian moralistic revivalist movement and traditional cultural nationalists were able to continue to promote their patriarchal claims to power.

TAC TB march, Cape Town, 7 November 2007. Photo: felix.castor /flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Lack of Political Will

In 2009, Jacob Zuma took over the presidential office, only stepping down in February 2018. He was personally responsible for numerous corruption scandals. But even before he took on the highest office of state, the judiciary had already had dealings with Mr Zuma who held leading positions in governmental AIDS bodies. In 2006, he was charged with having raped a young women. The trial ended in an acquittal but it set in motion a huge debate in society about sexual violence and HIV, especially since Zuma’s accuser was known to be HIV-positive. Zuma presented himself as a pugnacious and tradition-conscious Zulu man and justified proprietary, martial sexual behaviour.

Under his presidency, the 2007-adopted national action plan against gender-based violence continued to be largely ignored, even though the intention was to halve the official rates of violence by 2015. Already in 2009 the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women demanded multi-sector plans with concrete timeframes. But the Zuma government dragged its feet in implementing laws against sexual and domestic violence and the political guidelines for their prevention.

Lawyers lamented the lack of finance and uncertainties in budgeting. Improvements were required to implement protection against violence and the right to health. Admittedly, points of contact for victims of violence were established in police stations and female police officers were trained as contact persons, since aside from murder and robbery, rape remains the most frequent criminal offence and domestic violence is also very widespread. Even the police themselves in their annual statistics still assume that there is a high number of unreported cases of gender-based violence. Post-exposure prophylaxis is intended to prevent rape victims from becoming HIV-infected. But women’s and HIV organisations continue to report problems that rape survivors are facing in gaining access to state services. To what extent President Cyril Ramaphosa, in office since February 2018, and his ministries will change this situation remains to be seen.

Body maps: Khulumani support group. Photo: Rita Schäfer

HIV infections via rape are still not a thing of the past. At the same time, the negotiating power of women in many intimate relationships is so low that their partners react with physical violence if they ask them to use condoms. Gender-based violence thus, in several respects, prevents the realisation of reproductive rights. State institutions are called upon to become active in both consultation and prevention.

| Statistics: Gender-Based Violence South Africa | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of recent intimate partner violence among women aged 15-49 |

5.1% | Source: South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012 |

| Prevalence of recent intimate partner violence among women aged 15-19 | 7.3% | Source: South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012 |

| Prevalence of recent intimate partner violence among women aged 20-24 | 7.7% | Source: South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012 |

| Prevalence of recent intimate partner violence among women aged 25-49 | 6.4% | Source: South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012 |

Source: UNAIDS, South Africa, DATA: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica

Innovative Gender Organisations and Approaches to Prevention

At the same time only a few newly founded men’s and gender organisations are using the legal framework and state gender policy guidelines as a basis for their own practical approaches. They define themselves as agents of change in the context of processes of social transformation. Among them is the Sonke Gender Justice Network.

Members of Sonke reject constructions of masculinity predicated upon a readiness to commit violence and are working to change the attitudes and behaviour of men and boys, for example, via peer-groups of boys and men of the same age. In the face of high unemployment rates, innovative prevention measures are necessary to reach these men. Using new peer groups in which like-minded people come together, Sonke attempts to put changes in motion via imaginative media campaigns and statements from respected religious and local authority figures. One of its big challenges is to work together to formulate and disseminate new concepts of responsible and social fatherhood, violence-free partnership and masculinity.

Sonke Gender Justice 10 Year Anniversary Film

In doing so, Sonke sees itself as a cooperation partner of women’s rights and HIV/AIDS organisations like TAC. However, in this collaboration the following needs to be taken into account: competition for funding from international development organisations leads to latent conflicts. This is because, since the end of the 1990s, donors have given less and less support to women’s rights work in preference for selected HIV/AIDS programmes. Many donors have even withdrawn entirely from funding South African organisations and demanded more government services.

However, civil society organisations are dependent on outside financial support, particularly because they advocate their own stance in opposition to the government and even call for the implementation of official targets and guidelines as well as the constitutionally guaranteed rights, including to health and protection against violence. Thus the medium and long-term efficacy of their work in anti-violence, women’s rights and HIV prevention is not only dependent on national political and domestic social dynamics but also on the value ascribed to this important work by international donors.

Rita Schäfer: freelance researcher and gender consultant in South Africa and southern African countries. https://www.liportal.de/suedafrika/

Referenzen

- UNAIDS: South Africa: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica

- HIV and AIDS in South Africa: https://www.avert.org/node/404/pdf

- Afrika Check: FACTSHEET – South Africa’s crime statistics for 2016/17: https://africacheck.org/factsheets/south-africas-crime-statistics-201617/

- STATS SA – Statistics South Africa: Category Archives: Crime: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?cat=26

- Sonke Gender Justice is a non-partisan, non-profit organisation, established in 2006: http://genderjustice.org.za/